EDITION: CLASS.

“The excitement I feel looking at the 1960s architecture of Kenzo Tange is rooted in the excitement I felt as a six-year-old boy looking at the animated Autobot City.”

“You know what I did this morning? I played the voice of a toy. Some terrible robot toys from Japan that changed from one thing to another. The Japanese have funded a full-length animated cartoon about the doings of these toys, which is all bad outer-space stuff. I play a planet. I menace somebody called Something-or-other. Then I'm destroyed. My plan to destroy Whoever-it-is is thwarted and I tear myself apart on the screen.”Orson Welles, 1985

Real and Imaginary Robots on Southampton Docks

Memory is unreliable, and childhood memories are the most unreliable of all. Something has to have been quite monolithic in what you have left in your head for you to be absolutely sure it was important. So what I remember caring about from the ages of five and ten was the American toy and television franchise Transformers, more than almost anything that was happening in the actually existing world. A while ago, I wrote very briefly about this pre-pubescent obsession, one that I shared with many thousands of boys born around the turn of the 1980s. The setting for this was a description of Mayflower Park, a small 1960s public space in the city of Southampton. Named after the Pilgrims that left here to settle what would become the United States of America – they only got as far as Plymouth, where they rested before setting out again more successfully – it was and still is the only publicly accessible stretch of waterfront in that English port. It stands between a florid, domed and then-derelict Victorian pier and the concrete and red brick grid of the (recently demolished) Solent Flour Mills. The park was laid out with slides, a concrete maze, a short promenade, and vaguely Frank Lloyd Wright-like shelters from the wind, most of which have since been removed.

I would visit Mayflower Park with my brother and sister three Sundays a month, the designated days my dad had custody of the three of us. I associate my Transformers fixation strongly with this place, and with the struggle to reconcile the actual environment around me with the incredible and exciting world of Cybertron and Autobot City, and the eternal cosmic battle between the Heroic Autobots and the Evil Decepticons. This had reached inadvertently comic proportions already, when sometime in 1985 or 1986 I went home from my first encounter with religion – presumably an RE class or hymn practice – to tell my mum that ‘today at school we learned about this robot called God’. My interpretation made complete sense, of course. If you’ve not already encountered the idea of a creating deity – and coming from three generations of committed and active Marxists, I had not – then it is logical to assume it’s something a bit like, if you’re lucky, Alpha Trion, and if you’re not, the Quintessons. Certainly there’s no reason to think that we, weak, ill and fleshy, could have been made in the image of such a creator.

I moved on from this to insisting for much more inexplicable reasons that I in fact was a Transformer. This was more simple wish fulfilment, an anxious infant version of Marinetti’s grotesque ‘coveted metallisation of the human body’, and a portal to a more interesting and exciting world than the straggle of Southampton and Eastleigh, the reconstructed post-war city and adjacent Victorian railway town I moved between every few years. I identified most, like many bullied children in the 1980s, with the yellow Volkswagen Beetle, Bumblebee. He is described in The Transformers Universe as “physically the weakest of the Autobots”, but he “can go where other vehicles do not dare, because he does not look threatening”. With a direct line to the childhood psyche, the writers of that book add: “more than anything, Bumblebee wants to be accepted, and this sometimes causes him to take chances he shouldn’t”.

From Mayflower Park, looking towards the Flour Mills, you could see container ships, container cranes, and the stacks of containers housing the goods themselves. Southampton industrialised late, but when it did so, in the 20th century, it was in a big way. In the 1980s, most of my close relatives worked in factories. Dad was a skilled sheet metal worker at Bicc-Vero, which to me sounded very futuristic, and was one of the many reasons I idolised him. One uncle drove a (surely semi-transformable) forklift at the same factory, and another worked at the Ford transit factory (demolished), while my then stepfather worked on the production line of Mr Kipling’s Cakes. The Vosper Thornycroft shipyards (demolished) were visible from the derelict pier. At the heart of it all was the port, privatised that decade — a move which, along with containerisation, caused massive lay-offs. Here, finished goods from newly industrialised nations were literally piled up until, eventually, by the 2000s, they would put all these factories out of business. Whatever it was I thought I was, the robots were right there, in the form of the semi-automated container cranes and their attendant infrastructure, which maintained an elaborate ‘just-in-time’ system of distribution through computers, precision engineering and the extensive elimination of human labour. They even looked a little Transformer-like: metal, chunky, ungainly.

In recent years, British writing about childhood media – and the politics and production thereof – has been monopolised by people born in the sixties or early seventies, and their memories, gloriously unreliable as all childhood memories are, of a precious public culture of improvement, gentle egalitarianism, popular modernism, and the persistence of folk traditions. Doctor Who, Bagpuss, The Clangers, Children of the Stones, The Changes, The Tomorrow People, et al and et cetera. By the time I was a four-year-old able to identify different television programmes, that public culture had been effectively destroyed. You could find it only in a few remnants: Morph maybe, or the wilfully eccentric productions of Manchester animators Cosgrove Hall, like Danger Mouse or Count Duckula; maybe also in right-on, GLC theatre-style adaptations of old tales like Maid Marian and Her Merry Men; but generally, the sentimentality of The Snowman was about as ‘quality’ as you were going to get. I grew up with a vague and hazy awareness of that culture only through my maternal grandparents’ house in Bishopstoke, with The Countryman on the table, a lush garden outside, and a bookcase stuffed with Puffin Books they’d accumulated in their many years as primary school teachers. Otherwise, I, like almost everyone else my age, grew up on children’s television that consisted largely of advertisements. In that period, this new Reaganite children’s culture crushed its well-meaning precursor beneath its die-cast metal heel – something you can see in the way that Ladybird Books itself moved from producing picture books that told you how a nuclear power station worked, or how to spot rare birds, into advertising toys. If you can’t beat them…

To say that Transformers was an advert isn’t a euphemism or an insult, but a statement of fact. Like Masters of the Universe, Thundercats, the Care Bears or My Little Pony, but unlike Mickey Mouse or Star Wars, the consumer goods were not the consequence of a set of film or TV characters, but the cause. These franchises were created to sell toys, and the producers made that breathtakingly obvious in the way they plotted the programmes, introduced characters, and created a deliberate continuity between the programmes themselves and the adverts that would run between them. In these, the ‘real’ product would be revealed, so that you could, as we did, loudly demand them from your parents. If you try an amateur self-analysis and peel back the layers that you’ve acquired, what you’ll find at the bottom isn’t some kind of truth about yourself, but a meaningless mess of advertising slogans.

Transformers’ creators (so to speak), the Rhode Island-based toy company (and Mr Potato Head inventor) Hasbro, were able to do this because of Ronald Reagan’s 1981 deregulation of American children’s broadcasting. By removing restrictions designed to ensure that shows aimed at children were kept free of product placement – for obvious reasons, it was expected this would lead to immense pressure from children on parents to buy toys – corporations could suddenly create entire shows that did not just contain product placement, but were designed from the off as ads for toys.

Over here, the BBC resisted the new franchises that resulted, but you could watch them all on ITV. Masters of the Universe was the first, notoriously introducing new characters almost every episode so that Mattel, the company that devised the show, could market a new toy almost every week. Transformers, the second of these new advertising-cartoon series, was more Frankensteinian, an opportunistic lash-up between a disparate bundle of extant Japanese toys, into which life was breathed by Marvel Comics writers and Japanese and Korean animators. It is hard to imagine any cultural product more cynical and less pure. Everything becomes nostalgia eventually, of course, and you can scan through Netflix and find semi-ironic (and sometimes faintly woke) new adaptations of early 1980s syndicated toy adverts such as Transformers, He-Man, She-Ra or Voltron, targeted right at those older Millennials who might want to watch souped-up, less stupid versions of their memories with their children. In any case, there’s no ‘hauntology’ here, no unfulfilled future that you can lament or find the remnants of. These are totally neoliberal artefacts, and the world these programmes helped build is the one we live in. Instead of the public modernism of Oliver Postgate or Nigel Kneale, we were raised on a culture created directly by the Reagan administration and produced by the new globalised trade relationships that replaced an industrial economy centred on northwestern Europe and North America. Because of this, Transformers are not an uninteresting way of trying to work out how exactly it is we got here.

Adam Smith in Autobot City

One shouldn’t expect World Systems Theorists to have immersed themselves in 1980s kids TV, but the story of how Transformers came into being has the character of a long anecdote or a chapter from some lost work of Giovanni Arrighi or Fernand Braudel, and so it’s worth a detour. The actual Transformers themselves – the robots, those semi-physical objects, designed and produced wholly by the Japanese toy company Takara – are prime products of the 1970s and 1980s boom in which, for the first time since the 17th century, an Asian country became the most technologically advanced and economically powerful in the world, and embraced modernity and futurism at a moment when much of Europe and North America were retreating culturally into the past. Transformers were essentially one of a couple of dozen Mecha anime franchises which emerged over the course of the seventies. The superficial resemblance between the entirely unhip Transformers and the robots in much more demanding, sexually charged and dystopian franchises such as Macross and Gundam, beloved of the true western anime heads, is in no way coincidental – they were mostly devised by the exact same industrial designers, such as Shōji Kawamori, Kunio Okawara and Shinji Aramaki.

From a successful adaptation of manga artist Gō Nagai’s 1972 Mazinger Z onwards, commercial anime producers such as Toei and Sunrise would spend a decade or so producing a constant stream of TV series starring robots that could transform into vehicles or spaceships — all with attendant toylines from manufacturers like Bandai, Tomy, Popy and Takara, all with extremely exciting names. UFO Robot Grendizer, Science Ninja Team Gatchaman, Brave Raideen, Divine Demon-Dragon Gaiking, Super Electromagnetic Robot Combattler-V, Beast-King GoLion, Fighting General Daimos, Super Electromagnetic Machine Voltes-V, Armoured Fleet Dairugger XV, Future Robot Daltanious, Lightspeed Electroid Albegas, Space Battleship Yamato, Space Emperor God Sigma, Mobile Suit Gundam, Video Warrior Laserion, Super Dimension Fortress Macross, Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross, Genesis Climber MOSPEADA, Round Vernian Vifam, Super Dimension Century Orguss. Futuristic, colourful, visually rich and, crucially, very very cheap, these series would sometimes be bundled together in the early 80s by American TV corporations, who would remove any clues to their foreignness. These included explicit violence and ‘fan-service’ nudity, religious symbolism, and occasional dark subtexts alluding to adult subjects such as nuclear war or fascism.

Sometimes there would be a simple rewrite, as when Gatchaman became Battle of the Planets and Space Battleship Yamato was repackaged as Star Blazers, but more often American companies would bundle different franchises together so that they could run long enough to qualify for national syndication in the decentralised US TV network. So in the late 70s, Shogun Warriors repackaged Grendizer, Mazigner, Raideen and Gaiking, then in the early 80s Voltron retconned previously non-existent connections between GoLion, Dairugger and Albegas, and the mildly edgier Robotech coarsened the fabulous Eurovision space opera of Macross and spliced it with Southern Cross, MOSPEADA, and the ultraviolent and sexually gratuitous straight-to-video proto-Matrix SF dystopia Megazone 23, rewriting dialogue, plotlines and characters as they went along. So it was already well established that American networks devoid of ideas would go to Japan to borrow them; the same was true in the toy industry.

The ultimate source of Japanese toy robots can be found in the aftermath of the Second World War, when Japanese imperial capitalism was first restructured and then set back on its feet by the occupying American army. The notion was that cheap, nasty, labour intensive and relatively low-tech work such as the production of metal toys would be apportioned to the USA’s new ‘allies’ in The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, and the resultant items would then be imported to the US. There are various stories claiming that the raw materials for the first generation of Japanese tin toys consisted of discarded food tins left by the well-fed American occupiers, with Californian tinned tomatoes apparently a particular favourite. This isn’t so implausible, given that the ‘Robby’ style robots showcased by Teruhisa Kitahara in his famous museum of tin toys – collected in the fantastical photobook Robots and Spaceships ––- do look like very slightly adapted cans, with their tubular bodies and shiny sheen. The first manga and anime robots such as the 1956 Tetsujin-28-Go are, accordingly, anthropomorphic tin cans. From this developed further outsourcing of toy production from the US to Japan, as plastic gradually replaced tin. Though the plastic toys often lacked the pulp futurist excitement of the wind-up steampunk tin bots later collected by Kitahara, they would, over time, adapt to Japan’s less boring pop culture requirements. The redesign and shrinking of the jingoistic American toyline GI Joe into the much more fun Henshin Cyborg, aka Microman, one of Transformers’ many ancestors, is a case in point.

Toys aside, the sort of full-spectrum marketing and relentless industrial streamlining that marked Transformers was also informed by the practices of Japanese capitalism. In his book Anime’s Media Mix, Marc Steinberg uses the example of Osamu Tezuka’s great manga/anime series Astro Boy (or to give its Japanese name, The Mighty Atom) as a way of explaining how anime producers worked more ruthlessly than American animators and toymakers in marketing their products. Tezuka, though remembered fondly for the kawaii humanism of works like Kimba the White Lion and Metropolis, and for his thoughtful, dark later comics, was resented greatly by other animators for some of the commercial innovations he brought into the industry — but the product was good enough to stand on its own. Astro Boy is a strange and sometimes moving series, centring on an extremely cute robot child who is distrusted and resented by those around him, despite regularly saving various similarly cute humans and animals (Tezuka was inspired to explore the series’ themes of alienation and suspicion by the experience of being punched by an American GI). Among the series’ enthusiasts was Stanley Kubrick, someone who recognised alienation when he saw it; at one point he planned on hiring Tezuka to work on 2001. But in order to make the series a success, Tezuka specified very limited animation, a much lower production standard than Toei—the ‘Japanese Disney’—were used to. This allowed the series to be made very fast and very cheap, at the expense of the animation workers. Tezuka also agreed to an aggressive marketing campaign that instantly put Astro Boy on a range of consumer items, from the expected tin toys to clocks, mugs, and various promotions. This would inform the dozens of mecha series of the seventies, which all came pre-packed with toys and tat. So, when Reagan deregulated children’s TV, there was already a precedent as to the immense profits that could be made.

There are two things that were unusual about the robot toys that became Transformers in this context. One is that they were robots without franchises. Transformers drew mostly on two toy lines which the American company Hasbro bought from Takara: Diaclone — which consisted of robots that changed into cars, trucks, planes, trains and, well, dinosaurs and insects — and Micro Change, an outgrowth of the aforementioned Henshin Cyborg, which featured not only tiny toy cars that transformed into cute, pocket-sized robots (like the proto-Bumblebee), but also robots that transformed into a bizarre selection of commodities, from guns to cameras to microscopes to microcassette players (and their cassettes). Their style was very close to that of the late 70s mecha animations, with each of these creatures in ‘robot mode’ boasting heraldic, helmet-like heads, articulated high-tech bodies, and strident colour schemes. To be hauntological for a brief moment, probably the only genuinely uncanny experience open to the Transformers nostalgist is to watch the original Japanese commercials for Diaclone, recently beautifully analysed on We are the Mutants. They all use stop-motion animation and detailed science fiction backdrops, which makes the toys look like they’re part of some dreamlike tokusatsu series, and leave so much more room for the child’s imagination. Instead of the heavily scripted battle between good and evil of the series, or the startlingly hard sell of the adverts that came between the Transformers cartoons, these commercials “let you, the viewer, project yourself, into the adventures”, to make what you wanted of them – truly a lost future for this extremely cynical project.

The Micro Change and Diaclone toys, often sculpted in die-cast metal due to the cost of plastic rising during the oil crisis, are delightful objects. Many are as fascinatingly odd as the tin toys of the fifties, something which explains a lot of their appeal as futuristic puzzles and anthropomorphic machines. Some are extraordinarily weird and disturbing – it is inexplicable that children were ever allowed to play with Gun Robo Walther P-38 U.N.C.L.E, or Megatron, as we know him, a realistically scaled gun that changes into an angry robot with a giant trigger for a crotch. But these creatures did not appear in their own cartoons — at least, not officially. Before 1983, when Hasbro proposed the Transformers project to Takara, some Diaclone figures had inadvertently become characters in South Korean aeni. Korean animation developed intensively in a brief period during which Japanese media were banned under the Chun Doo-hwan dictatorship. Already culturally and industrially close to their former colonial oppressor, and used to dubbing its anime series, Korean producers improvised by creating new products ripping off whatever they had to hand, borrowing characters from different anime and splicing them into new stories. So the Diaclone figure Fire Engine Ladder Car For High-Rise Buildings, soon to become the Transformers character Inferno, became the hero of the aeni feature Phoenix-Bot Phoenix-King. Translated and dubbed into English as Defenders of Space, the film is staggeringly cheap and joyously inept, something like the Plan 9 From Outer Space of anime. The American repackaging would be, at least, somewhat more elaborate.

The sheer quantity of the existing products licensed from Takara meant that Hasbro could, as Mattel did in Masters of the Universe, introduce at least one new saleable commodity with every episode (though soon even that was not enough, and Hasbro bought in figures from Macross and elsewhere, with complicated legal consequences). After their deal with Takara, Hasbro hired the Filipino designer Floro Dery and Marvel Comics writers such as Bob Budiansky to conjure up names, characters and a narrative, which was heavily Star Wars-influenced: an evil empire and a good resistance, emerging from a long time ago in a galaxy far far away, but crash-landing in the exotic land of Oregon, and, upon waking after millennia of slumber, deciding to assume the forms of Earth technology so as not to be noticed.

This brings to the fore another curious fact about Transformers – the robots were reimagined as sentient, and hence as friendly, almost-human. Although the original toys had niches in them for small human figures to ‘pilot’ them, they were, as replanned and repackaged by Hasbro, presented as characters, with individualised ‘personalities’. This placed them much closer to the poignant alienation of Astro Boy or a primary school Blade Runner, with the robots being thinking creatures that were at the same time machines.

The Korean connection went beyond the initial piracy of proto-Transformers in aeni films. The American series would initially be animated in Japan by Toei, but the improving standard of workers rights in that country meant that increasing numbers of episodes, and a feature length film, would be made in South Korea. Transformers The Movie was essentially made in Korea. Its director, Nelson Shin, was the head of the Korean animation studio AKOM, who would go on to animate practically every American cartoon of the nineties (up to and including The Simpsons). The toys themselves, as you can see when you pick one up and look underneath it, were made in similarly ‘emerging’ East Asian industrial economies where workers were at that time cheaper still, mainly Taiwan and Macau, and, by the end of the eighties, the People’s Republic of China. A particular interconnected economy emerges out of all this, in which companies in the USA, Japan, Korea and both Chinas apportion out brain work and hand work depending on the cost of labour in each country. Only the marketing strategy was the preserve of the Americans, who by the 1980s evidently no longer had the ability to imagine new forms and new worlds by themselves.

Robot Dad is Dead

What this meant when these toys made their way onto the screen was a staggering cynicism with regards to the child audience, which had rather unexpected consequences when those children began to project their own emotions, desires and fears onto the commodities. The notion of taking some Japanese transforming mecha toys and making a newly legal advertainment franchise out of them occurred to two American toy companies at once. First into the shops in 1983 was in fact Go-Bots, which was put together by tiny-truck-manufacturer Tonka and famed animators Hanna-Barbera, from one Bandai toyline, Machine Robo. The toys were simpler, cuter, cheaper, and sometimes funnier than the detailed and complex Diaclone toys Takara and Hasbro were importing, so the line initially sold well. The thing that killed Go-Bots was the comparative poverty, when compared with Transformers, of its attempt to breathe life into the inanimate commodities. Go-Bots also made the robots sentient, and also divided these unknowing, innocent consumer items arbitrarily into goodies and baddies, but its cartoon was nowhere near as effective in dragging children along with the project.

The fault here lies almost entirely with Hanna-Barbera. Watching the cartoon Challenge of the Go-Bots is painful because you can see in the crude line drawings, simple backgrounds and caricatured faces that the people making this had probably worked before on the formulaic but imaginative likes of The Jetsons, Wacky Races, Josie and the Pussycats, Top Cat and Yogi Bear, where limited animation met anarchic pop art, and disliked having to advertise a line of toys they had nothing to do with. The cartoon’s ultra-American style fit badly with the Japanese products, meaning there was no way of being swept up into a strange futuristic world – you were watching tin cans fight each other, and the scripts and voice acting showed a similar embarrassment from the makers that they had to stoop so low. The series was partly animated by Toei, after Hanna-Barbera’s own animators went on strike in 1982, but it couldn’t have looked less like anime. While Takara imported Transformers back into Japan, renaming it, in the national style, as Fight! Super Robot Lifeform Transformers, Bandai rejected the Go-Bots cartoon and made their own show with the Machine Robo figures instead (and pretty stylish it was too). The Go-Bots project ended in ignominy when they attempted to market Bandai’s line of transforming lumps of plastic rock as ‘Rock Lords’, advertised as ‘powerful living rocks’, and then made them the stars of a film featuring Telly Savalas as its star voice actor. Transformers The Movie had Orson Welles.

At the time, in the US especially, the decline in children’s TV that was symbolised by these toy shows was not lost on people. The shift from the gender and racial balance of Josie and the Pussycats or Scooby-Doo towards relentlessly gender-segregated programming where human beings, when they appeared, were almost entirely white, was one factor; but much of the discomfort came from the fact that the shows no longer had anything for the parents. From Looney Tunes onwards, a small but significant part of the gags in kids TV were deliberately aimed above the children’s heads, but Transformers has no concession to adults whatsoever – it is mostly mindbendingly witless, stupid and repetitive. That was of course part of these programmes’ appeal to children – they were completely part of your world, no grown-ups allowed. With that said, the failure of Go-Bots indicated that children were not passive receptacles for whatever corporations wanted to throw at them, and could pick, like Soundwave, between superior and inferior trash.

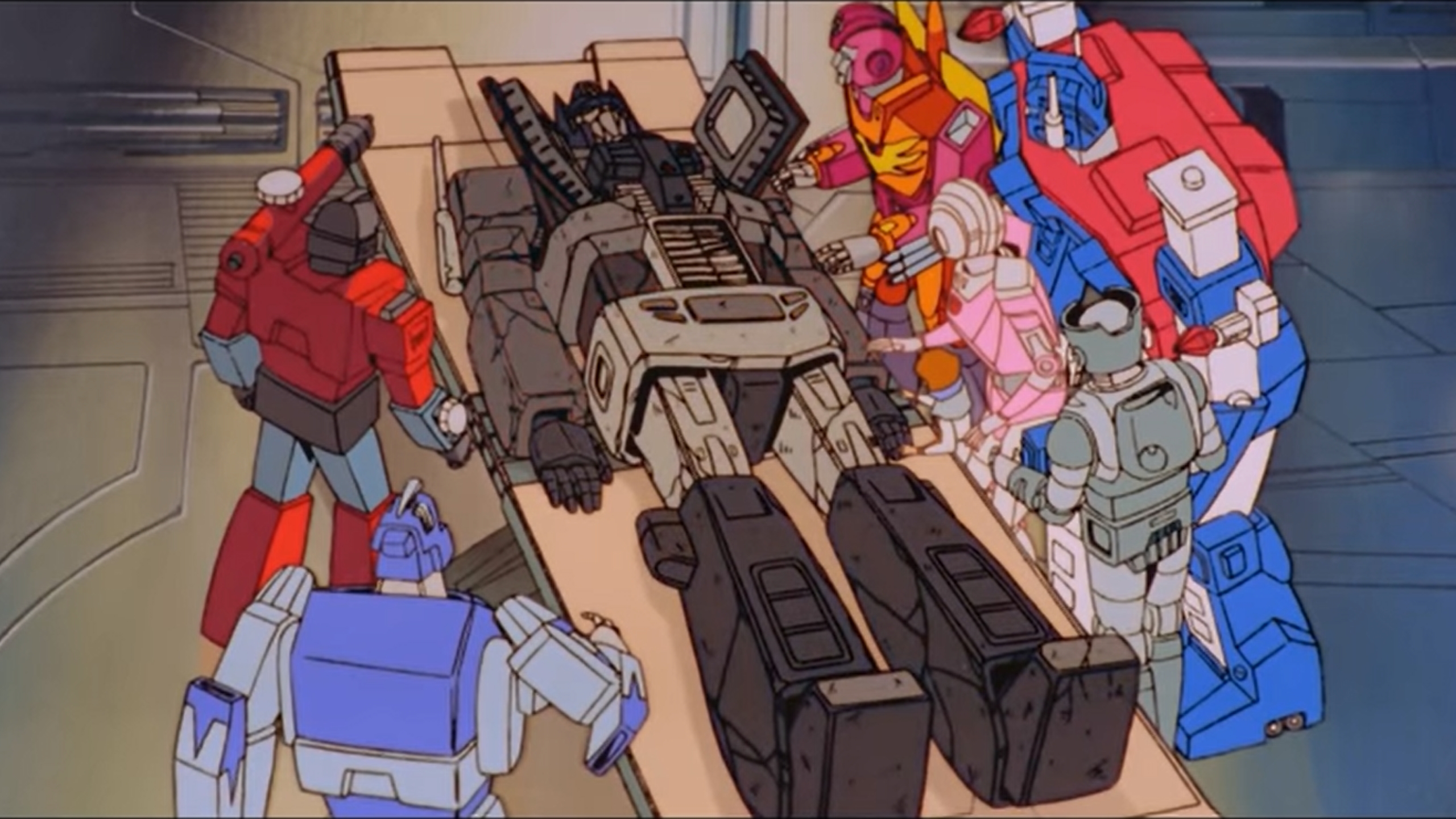

So the three and a bit series of Transformers are never good, as such. You can watch them all on YouTube, as I did when writing this, and though there are some moments of impressive pulp ludicrousness, it is made with considerable contempt for its audience. Comparing the humour, visual imagination and lively, sometimes satirically sharp humour of many sixties or seventies American cartoons (let alone the work of an Oliver Postgate) to this inane pap is very sad. There is seldom an attempt to hide what is going on – many minutes are taken up with new characters/new toys inexplicably appearing and announcing themselves, with only a handful being given a backstory to explain where they’d suddenly come from. Continuity errors are incessant. But there is, at times, an undeniable enthusiasm to it that explains how they managed to drill down into our brains. A lot of the effectiveness comes from the animation. It is limited and cheap, but bright and sometimes detailed, with some impressive cityscapes and shimmering and strange sets, such as the Autobots’ crash-landed ship with its flickering supercomputer, or the skyways and skyscrapers of their dead mechanical home planet of Cybertron — all of which are especially exciting given that lots of the action takes place in the desert. The impressive backdrops and colours come from anime practice. In something like Galaxy Express 999 the animation is as basic in terms of frames as anything by Hanna-Barbera, but the science-fiction backdrops, mostly unchanging and therefore cheap to animate, are ambitiously drawn to a Fritz Lang scale.

If this was a matter of Toei’s animators being given the opportunity to do their usual weird and interesting thing, the hilarious voice acting is thoroughly all-American. Frank Welker and Christopher Collins gave thoroughly villainous performances as various Decepticons, and Peter Cullen did a gravelly, paternal turn as Optimus Prime, in a way that was, in the end, a little too convincing. Transformers was keen to produce as much identification in its audience of young boys as possible. You often followed the events through the Autobots’ friends the Witwicky family, a typical Midwest working class bunch. As Michael Grasso pointed out in We are the Mutants’ discussion of Transformers, the world of the series was made as proletarian as possible, given that the expected audience was an America that was, if not industrial, then freshly deindustrialising. The series was intended for the young sons of factory workers, power station workers, and truckers, and that’s why much of the it takes place in factories and power stations, and why the main hero of the series is a Freightliner truck. What this means is that, as a working class child, you were seeing the commodity world and the built environment around you, the familiar cars and motorways and smokestacks and office blocks, being literally animated and transfigured. Rather than being something your dad would drive that was made in the factory down the road, this car is actually a sentient lifeform from a distant metal planet! There’s even a 1970s energy crisis subtext, in that the Decepticons are constantly trying to mine enough ‘Energon’ to be able to fly back home to Cybertron and then mmwwaaa haa haaa haaa conquer the entire universe!!!

The most common experience for children who came unprepared to a screening of Transformers The Movie was to have their first experience of grief: a profound emotional hit produced purely by accident, for the most brutal commercial reasons. My parents never minded me watching the show – mum was keen that I didn’t watch war cartoons, and would have been horrified if I’d developed the same obsession with GI Joe: but enjoying watching giant robots fighting each other in a desert or on a cybernetic planet was not considered likely to make me into a violent imperialist as an adult (irrespective of the fact that the series was, well, deeply imperialist); and so she reluctantly tolerated me saying in an undertone ‘I want that, I want that, I want that’ during the ad breaks. Similarly, she was happy to take to see Transformers The Movie at the (since demolished) art deco Odeon on Above Bar, in the centre of Southampton, sometime in 1986 or 1987.

There is a great deal to like about it as a work of spectacle. Nelson Shin was clearly given a large budget, and spent it on such immense, glittering tableaux as a multilayered, Metropolis-like Cybertron, and the devouring interior of the planet-eating planet Unicron. There’s a soundtrack that veers between synth-goth themes and hair metal anthems, there’s the spectacular last performance by the man Michael Denning called ‘America’s Brecht’, and there’s a wealth of weird new protagonists, such as the Quintessons, a group of fascistic Assyrian robot-octopi, and the Junkions, babbling Eric Idle-voiced robots who live in rubbish and ‘talk TV’ – a rare acknowledgement there from Hasbro of the mountain of meaningless plastic they were stuffing in the heads of the west’s children and the vaults of the world’s landfills. It is notorious that in the first twenty minutes of the movie nearly the entire cast of the television series you had been watching for the past couple of years were killed horribly and suddenly, something which has not exaggeratedly been called an ‘extermination’. Most of them are killed without ceremony, but lingering, high tragedy deaths are reserved for Megatron and Optimus Prime. The latter in particular is given a Christlike dying speech and a horrifying fade to grey, as the machine stops and the child Daniel Witwicky weeps, as you will have wept.

What made this so shocking was that most episodes of the show involved some enormous fight between these two, and inevitably neither of them would die and would fly off to do the same thing next week. The rules were now inexplicably broken, and the great heroic fatherly truck, who was committed to fighting for “freedom, the right of all sentient beings”, beloved comrade of Spike and Daniel Witwicky, just…died. If you hadn’t been bereaved before (and I hadn’t), this was quite straightforwardly a gratuitous exposure to a beloved father figure being killed — and do I need to spell out quite how much this went straight to the anxious core of a child whose parents had divorced a couple of years earlier, and who believed his forcibly mostly absent dad was a freedom-fighting industrial hero? This wipeout happened, of course, for a very simple reason indeed, and that’s the fact that Hasbro and Takara wanted to clear the previous two years’ products off the shelves, and shift an entire new range of commodities to six-year-old boys everywhere. The American scriptwriting team writing this Korea-made movie decided that, because they didn’t care much for these characters (why would they, given that they were literally animated toys?), neither would the children. They genuinely didn’t predict the enormous outpouring of pre-pubescent grief that would ensue, a wave that would force them to eventually resurrect their beloved fatherly truck Christ. But they would have to kill him again.

Is This…Anime?

The third series of Transformers ran after the film, and experienced a certain level of decline, largely because of the fact that Hasbro had killed off a huge part of the original cast. In some cases, toys had been so popular that they remained on sale, which meant that they had to be shoehorned into the plot as ghosts, a device which was used for the earlier series’ cyborg Ozzy Osborne villain Starscream, and of course for Optimus Prime, in a frankly very eerie episode in which his corpse, floating through space, is turned into a machine zombie. By the end of the series, pressure from the children who were still watching (expressed both through a letter-writing campaign and the findings of Hasbro’s many child focus groups) meant that Robot Dad was resurrected. In any case, watched today, as an adult, the third series is by some distance the most fun. It was also my favourite as a child. By now, you’re in the distant unimaginable future (the year…2006) and the commodities have long since floated free of reference to the existing industrial world. Most robots change into ‘Cybertronian vehicles’ or into monsters, rather than into familiar cars, planes or consumer goods. The music has changed from horn-parping TV cues into synth-rock epics, especially a frankly banging theme tune; our heroes and villains are usually floating through space and seldom even fighting each other (Megatron, reincarnated as the purple, crown-wearing Galvatron in the film, is depicted as severely mentally ill – a consequence of his earlier tussles with Orson Welles – and hence is distrusted by his fellow Decepticons). There is a lot of background, focusing on the Transformers’ creation by the cyber-mollusc Quintessons, creatures whose story and image are borrowed largely from Quatermass and Doctor Who (but I wouldn’t have known that).

It is maybe curious, given how much the earlier series had tried to create a sense of familiarity to hook the children, that I preferred this departure from reality. Looked at today, it’s clear how much this series – though increasingly animated in Korea rather than Japan – is basically anime, with the rich visuals carrying SF plots which condense familiar dystopia or disaster tropes into 22-minute kids’ tat (I still shudder at ‘The Hate Plague’). A fourth series was commissioned but ran to only three episodes, made almost unwatchable because the scriptwriters had to cram the entire 1988 toyline into around an hour, whilst also introducing 46 new toys/characters. I am still grateful to it for teaching seven-year old me the difference between ‘meritorious’ and ‘meretricious’. At this point, the series was cancelled, and though toys still came out regularly, Transformers was clearly on the way out as a franchise. I was a highly loyal consumer of Hasbro’s product, but even I knew the writing was on the wall when the Marvel comic book, still available in every good newsagent, was merged with the wholly uninteresting GI Joe. In Japan, there was no decline of interest, and so Transformers continued for another three entire series. I didn’t know this at the time; insofar as these three were available to western children at all before the internet made everything instantly available, it was through a notorious English-language dub made in the 1990s in Singapore. This frankly enhances the experience of watching the first of these, Headmasters, which is a straight retread of series three, only phasing out any of the interesting characters (and killing the resurrected-by-popular-demand Optimus Prime a few episodes in). The surrealism of the dialogue is the main reason for anyone who isn’t either incredibly bored or incredibly nostalgic to watch the series. There are some notable differences with the American product, though. Along with the lack of sentimentality towards the characters, there are much longer and more elaborate sequences of transformation, and there is a more terse approach to dialogue. In the American Transformers, a character will quip ‘see you later, auto-klutz’ or ‘not so speedy are you now, decepto-creeps’ before shooting them in the face. In the Japanese series they will yell ‘GOD ON! ! !’ or ‘CHOKON FIRE GUTS! ! !’ before doing the same.

What is also notable is the focus on young human Daniel Witwicky, who has many and varied adventures therein. Here we arrive at the main innovation of the Japanese series. The scriptwriters of the TV series were aware that it wasn’t necessarily enough to make kids identify with the other kids on screen who got to hang out with giant transforming robots; you might, as we’ve seen, identify with the robots themselves, as small me very much did. You yourself might want to transform. So Spike and later Daniel Witwicky are given occasional plots in which they have little robot suits that enable them to transform into vehicles; in Headmasters, the end credits sequence burlesques this by having Daniel and his father Spike try to transform into various things only to fall over, as the song cries ‘you are a transformer!’ Toei ran with this idea in what is the most enjoyable Transformers series of all, Super-God Masterforce, the second of the three Japan-only seasons. Aside from some token attempts in the first few episodes to establish continuity with Headmasters, Super-God Masterforce is, in the later parlance, a ‘reboot’.

The scriptwriters, who had all worked on other mecha anime from Gundam to Yamato, combined the American idea that Transformers would be sentient, sentimental creatures with the Japanese norm of giant robots that are wholly controlled or piloted by humans. So while the Autobots are still around fighting for freedom and whatnot against increasingly monstrous Decepticons, they often hide in human form (both the Autobots-hiding-as-humans and the Decepticons-hiding-as-monsters were marketed in the US and Europe in the otherwise inexplicable ‘Pretenders’ toyline, in which plastic Russian doll humans or monsters conceal tiny Transformers). Via some complicated technology and some brief exegesis they teach three teenagers, two boys and one girl, to become Transformers themselves. Also hanging around are the Godmasters (again, on sale in Woolworths, as ‘Powermasters’): human beings who are secretly and unknowingly Transformers, imbued with power beyond that of any other Transformers. One of these, a Sid Vicious-haired young man called Ginrai, becomes Super Ginrai and then God Ginrai, and looks exactly like Optimus Prime for reasons that are in no way explained (again, the resulting toy was sold over here, as ‘Powermaster Optimus Prime’). None of this makes a great deal of sense, but it taps into the sort of themes you would get in any other 1980s robot anime, with intense teen angst about everything from the opposite sex to the divide between the human and the non-human increasingly going alongside the more pre-pubescent concerns. Super-God Masterforce also frequently looks fantastic, with detailed cityscapes, monumental mecha, monsters, and a colour scheme full of bright, dayglo and pastel late 1980s acid house pinks, blues and greens.

This lost (to Europeans and Americans) future of the Transformers is not the one that actually came to pass. In Europe and America, the figures would be phased out from the shelves, return for a bit in a show in which the Transformers change into animals, then be revived as Generation X nostalgia in Michael Bay’s technologically overwhelming and even-stupider-than-the-original CGI/live action film series. In Japan, there’s another, slightly different timeline, one that has some wormholes that you will regret going down. The last of the original Japanese series, Victory, is another giant robot anime, though a somewhat less weird one than Super-God Masterforce. Then, as the brand had clearly become stale even in a market where there was no small interest in giant robot TV shows, it was simply renamed, and turned into the long-running anime series Brave, using the same staff and the same ideas and in some cases the same toys. The Brave series, which ran for over a decade, went back to targeting younger children, and because the name had changed, the producers could act as if the idea was completely new (the first episode is called ‘Our Family Car is an Alien!?’. It’s fun and prettily animated, and most notable for being the source for the famous ‘….is this....?’ meme, and for having an entire series, Brave Express Might Gaine, devoted to transforming trains, a theme that ran through Japanese Transformers, but seldom the American series (cars from space are one thing, but in a country that doesn’t have a Shinkansen, Raiden would need too much explaining). There’s still plenty of kids’ anime today in a very similar vein, including one series that is literally sponsored by Japan Railways as a means of getting children excited about railways, which we can all agree is better than getting them excited about Porsches or trucks.

We Think TV!

By the time of Brave, mecha shows had long since grown up into Ballardian SF like Patlabor or the apocalyptic and abstract hormonal-depressive terror of Neon Genesis Evangelion, and the Japanese idea that you could market cartoons with thoughtful subtexts, lashings of ultraviolence and extensive leering finally reached the US and Europe, creating a generation of weebs: which is another story entirely to this one. But the fact remains that the Transformers arc from the start to the end of the 1980s fairly accurately represents not only an industrial shift, but a shift in freshness and creative ideas in commercial artforms (such as cartoons and toys) towards Asia, with much American culture concentrating on various forms of computer-generated nostalgia. Again, this is a shift which is now entirely accepted and normal; the world we now live in.

Someone who knew exactly what they were looking at would have been able to see that shift just through tracking the goods that came into Southampton Docks between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s, a decade during which an industrial city became a post-industrial one. The part of the dock complex that continued and thrived after containerisation was laid out on reclaimed land in the 1930s, and inland consisted of a sprawling industrial estate next to the Central railway station, with the aforementioned Flour Mills, a Pirelli cables factory (demolished, for one of Britain’s largest shopping malls), and a power station. The latter was demolished in the early 1980s and replaced with a Toys R Us, in a big white box, indistinguishable from the newer automated warehouses of the container port. A visit was the highlight of any Sunday, and I remember oddly acutely its hierarchy of toys, and how the deeper you went into it the more likely you were to find cheaper, tattier Japanese toys that were no longer top-line, like Voltron and Go-Bots and eventually Transformers themselves, with the really expensive, high-end stuff – video games and bikes – at the front.

In the 1990s, our household went from just about coping to poor. But having a father who earned a decent skilled wage and paid only maintenance meant I could get the toys I wanted every Christmas. The fact he was convenor at Bicc-Vero and a leading member of the Trades Council meant he could call in favours – free tickets to games at the Dell sometimes, and first dibs on the new items that came in off the ships into Toys R Us at others. The last Transformer I remember getting for Christmas was Overlord, a foot-high thing which transformed both into a city and into a spaceship, and appeared in no cartoons over here (it was, I would learn 30 years later, a figure from Super-God Masterforce). After that, I had briefer obsessions with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Southampton Football Club, and Manga Mania magazine, before settling in my mid-teens into a typical middle class taste for music and the music press, beatnik literature and mildly arty cinema. Childish things were put away, for the benefit of the cause. The plastic tat of my childhood, stuffed into a big empty Duplo box, was sold off to Militant’s Fighting Fund. I wasn’t bothered to see it go; but if only Militant had known to wait for eBay, they could have funded a few years worth of paper sales.

It was widely argued at the time - including by commentators on the left such as Stephen Kline in Out of the Garden, an intelligent book on Reaganite children’s culture - that these artefacts would do permanent damage to children’s development, leaving them unable as adults to differentiate between art and advertisement, between commodities and useful things; and ultimately leading them to live in their heads, in a fantasy world. I can’t say any of this was entirely untrue: I am susceptible to all of these things, and so, probably, are you. As much as I might root it in a love of my hometown’s heroic Brutalist social architecture, I know that the excitement I feel looking at, say, the 1960s architecture of Kenzo Tange, is rooted in the excitement I felt as a six-year-old boy looking at the animated Autobot City. All of us – except perhaps a handful of people with exceptionally pushy and vigilant middle class parents - are like this, and our dreams are not entirely our own. Perhaps in that dream of transformation, and of commodities that can think for themselves, there is something that can be redeemed.

On the boxes of early Transformers toys — these objects designed in animation sweatshops in suburban Seoul and Tokyo, made by underpaid and overworked labourers in factories in Kaohsiung, Macau and Shenzhen, marketed by hardened capitalists in an office park in Pawtucket and dropped off at Southampton Toys R Us — there are, alongside a gorgeous painting of various die-cast commodities floating in space fighting each other, the following words: ‘IT IS A WORLD TRANSFORMED, WHERE THINGS ARE NOT WHAT THEY SEEM’.