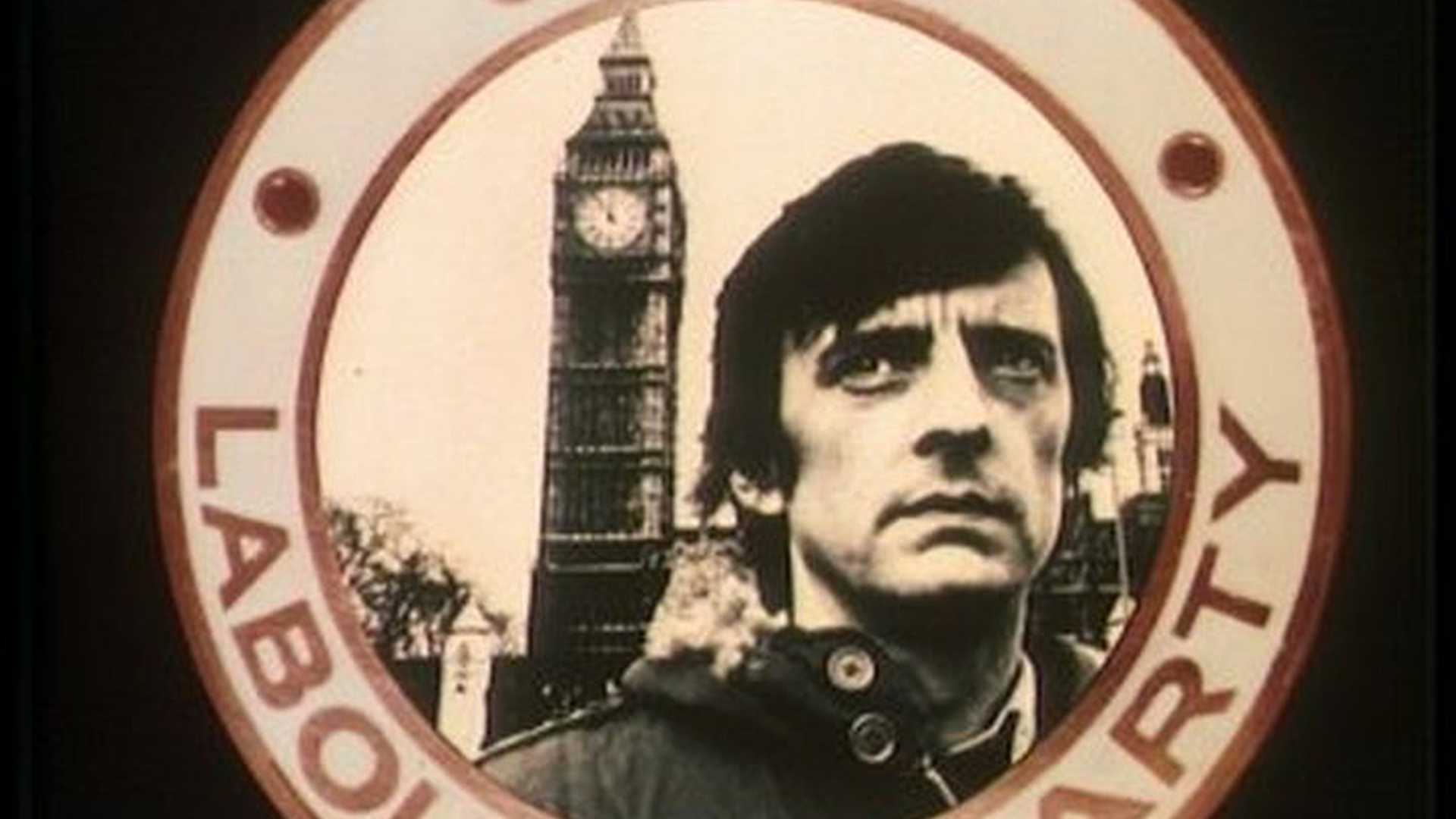

Four decades on from its debut, Trevor Griffiths' newly-relevant 'Bill Brand' remains a work of unusual political rigour and depth.

More than four decades on from the debut of Trevor Griffiths’ Bill Brand in summer 1976, and looking at the comparatively meagre pickings of today’s political TV drama landscape, it seems incredible not just that a work of such unusual political rigour and depth (and from the pen of a Marxist playwright) went out on prime-time ITV, but that it got any airing at all.

Both Griffiths and the series’ cast and crew had to fight hard for its 9pm slot. While Bill Brand was still in production, ITV aired another series focusing on the trials and tribulations of a Labour MP, Arthur Hopcraft’s The Nearly Man. As a result, scheduling controllers wanted to push Bill Brand back to a 10.30pm slot instead - only for the programme’s production team to arrive en masse to protest, forcing a rethink. As Griffiths himself emphasised: “my class, the people I want talk to, don’t watch from 10.30pm, because they have to get up at half past six to go to work”.1

But where the relatively sedate The Nearly Man depicts the faltering career of a jaded, embittered protagonist - a rightwing Labour MP clinging onto his seat largely in the fading hope of securing a senior Cabinet post - Bill Brand plunges the viewer headlong into the turbulent early career of a pugnacious young radical, highly suspicious of the trappings of office, determined not to become ‘lobby fodder’ and fervently committed to advancing the welfare of the people who sent him to Parliament. Brand faces battles left, right and centre, with the whips, in his constituency Labour Party (CLP), in the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP), with the party leadership, trade union officials and leaders, and party whips - all before he gets to seriously tangle with the Tories.

Regularly reaching an audience of over 11 million,2 Bill Brand was part of the wave (and perhaps marked the crest of that wave) of unabashedly radical TV drama which hit British screens in the 1960s and ‘70s. Griffiths himself, though also celebrated for his work in the theatre, considered televisual work a crucial priority, holding as it did the potential to put forward socialist critiques to a mass audience (helped by the fact that there were still only three TV channels in Britain in the mid-’70s). The strength of the labour and working-class movement, and the prominence of its associated culture, in this period also opened up opportunities for radical playwrights on the small screen. While socialist ideas and perspectives have of late made something of a return to the national political arena, Britain’s cultural landscape has yet to reflect this. TV drama remains, perhaps ironically, something of a closed shop.

It isn’t just the renewed relevance of the subject matter, but also the meticulousness, attention to detail and scope of Bill Brand that means this series continues to offer us pointers with relation to the political challenges socialists face in the here and now. Griffiths shines a light on the otherwise obscure internal machinations of the Labour Party, which on the face of it might not seem like the most gripping source material for a TV drama (at least for those who aren’t already of a certain persuasion), but which in fact are racked by ongoing tensions and conflicts.

In Bill Brand, Griffiths depicts a Labour Party, and a wider labour movement, at risk of finally breaking down under the weight of its various contradictions - not just the intensifying battles between left and right in the party, but also the tensions between left MPs and left party members, between the Labour Party left and left trade union leaders, between trade union leaders and their own rank-and-file, and between Labourist orthodoxy and the demands of the burgeoning social movements outside Parliament for meaningful equality. Griffiths’ achievement was to produce out of all this a drama of exceptional and enduring quality, and one from which we can continue to draw valuable lessons in the Corbyn era.

“You See This as a Sellout, Then?”: Brand, Griffiths and Labourism

The genesis of Bill Brand came on election night in 1974, with Griffiths and producer Stella Richman meeting in a restaurant owned by the latter to discuss potential ideas for a new project. As Griffiths tells it, their chosen venue was:

…full of those reactionary showbiz people, who’d all had a bet with Ladbrokes on the Tories pulling it off. And, as the evening progressed and the results came out, it was amazing to watch these fuckers break down in tears and begin wailing.3

He suggests that it was the ‘wailing’ of his fellow guests that gave him the inspiration to write “something on politics, on Parliament”, which he pitched to Richman there and then. However, Griffiths’ interest in Labourism had been rekindled somewhat earlier, with another TV play on the subject (All Good Men) having aired in January of that year. Griffiths had briefly been a Labour Party member in 1964-65, and despite rapidly becoming disillusioned by the first Wilson government, had been considered a potential parliamentary candidate. It could be argued, therefore, that the earliest seeds of Bill Brand had in fact been sown then.

Like Griffiths, Brand is part of the generation of upwardly-mobile, young working-class produced by the 1944 Education Act and post-war social democracy. He makes his entry into frontline politics as the social compact which gave him his start is visibly crumbling; the textile industry which gives his constituency (the fictional Greater Manchester satellite town of ‘Leighley’) its lifeblood is on the brink of disappearing altogether. Brand sets himself the goal not just of saving the industry by pressuring the embattled minority Labour government into taking it into public ownership, but over and above that striving for “the elimination of all eliminable inequalities - not just here but abroad too”.

With the twin spectres of neoliberalism and globalisation looming large, the contradictions of these aims soon make themselves apparent. In the series’ third episode, Brand asks a migrant textile worker what will happen to his relatives working in the Lahore mills if cotton import quotas are halved to help save the industry’s British workers from the dole queue. The worker tells him somewhat phlegmatically that it would inevitably cost them their jobs; capitalism endures precisely by turning “worker against worker” in this way, he adds.

A deep-seated ambivalence towards the Labour Party as a potential vehicle for socialist transformation continually troubles Brand. This ambivalence extends not just to the party’s right and centre but its left as well, particularly its parliamentary left. Immediately upon entering Parliament, Brand is the subject of appeals to join the ‘Journal Group’ (a thinly-veiled stand-in for the real-life Tribune Group of Labour left MPs) but initially rebuffs them despite taking up residence in a houseshare alongside several Journal Group MPs. At one point, Brand clashes with housemate and fellow MP Winnie Scoular, perhaps the Journal Group’s most radical MP alongside himself, about its decision to allow its members to take up frontbench posts:

There is a million-and-a-half unemployed out there, Winnie. That’s not an act of God, it’s an act of Government. People’s lives are being sliced into ribbons in this pathetic attempt to shore up the crumbling edifice of British capitalism, which is, of course, the historic function of this great Party of ours. And comrades - Journal people - preside over it all, locked away behind their ‘collective Cabinet responsibilities’, out of reach. On the other side.

In fact, the frustrations Brand articulates here were very widely felt on the extraparliamentary Labour left in this period. Not only did the Tribune group make no serious effort to build up a base of support at the party’s grassroots, but it took little action to discipline those MPs who chose not to abide by its collective line on particular issues. As Patrick Seyd has observed, a lot of the MPs who joined the Tribune group did so largely to keep their leftwing constituency parties satisfied.4 It was to a large extent this dissatisfaction with the left of the PLP which would usher in the struggles over party democracy and accountability that gripped the Labour Party in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. While the exact forms those struggles would take (mandatory reselection, ending the PLP’s monopoly on leadership elections, putting the NEC in charge of writing election manifestos) aren’t prefigured here, the seething resentment which gave rise to them is present and highly palpable.

Like countless other socialist MPs before him, Brand’s great fear is that of becoming imprisoned by what he terms “the metallic logic of social democracy”, leaving him and the rest of the parliamentary Left helpless and hapless as their own government attacks working-class living standards and the social wage to restore private profitability, “unable to do what is incontestably right because their definition of the Left ends with a Labour government, which they must keep in power at all costs”:

A Labour government, kept in power by the likes of me, is currently fulfilling - yet again - its historic role as the supreme agent of international capitalism in Britain. And all the classic features of this process re-emerge: chronic large-scale unemployment, massive sustained cutbacks in public spending - you know, education, nursery schools, hospitals - coupled with the steady, sheltered recovery of profits in the private sector… And what do I do? I treat Parliament, this, as an arena for the exercise of moral repugnance. Like any liberal.

Brand is sought after as a potential Parliamentary Private Secretary by employment secretary David Last (a stand-in for Michael Foot), a veteran radical albeit one whose socialism is widely suspected to have faded during his time in the Cabinet. Brand himself, a longtime admirer, views Last’s decision to take up his Cabinet job with suspicion and not a little disappointment. Last himself is conscious of this, noting with dismay the tendency for Labour governments to “squelch about like shysters and milksops when it comes to translating our programmes into realities” and putting the question to Brand: “You see this as a sellout, then?” But Last’s justifications for leaving the backbenches are, like Brand’s for joining the Labour Party and entering Parliament, largely pragmatic5 - though no doubt also tinged with a sneaking personal ambition: “I just felt I no longer had the right to say no. It doesn’t ever just happen. It has to be made, and it has to be led.”

This nagging sense of continually running up against structural limits pervades Griffiths’ work on Labourism - not just Bill Brand, but also All Good Men and Food for Ravens, his 1997 BBC TV play on the final months of Nye Bevan’s life. In episode six, Brand’s election agent Alf Jowett - having devoted two decades of his life to a party which has singularly failed to deliver the socialist reconstruction he still yearns for - drunkenly despairs at the lack of progress it has made in this direction: “So what have we achieved, eh? Twenty years of struggling and arguing and wheedling and bullying and hustling and chiselling and promising and welching and offering and not delivering.”

For his part, Brand tries to probe and push back these limits, aiming to broaden the horizons of Labourism by building up the extraparliamentary movement and fostering the growth of popular power. His conception of this remains rather embryonic, but the fact that it appears at all is one factor which sets Bill Brand apart even from other TV dramas written from the left, such as A Very British Coup. In episode eight Brand argues, in conversation with his brother, that “we’ll do nothing unless we’re made. And the only power we have is what you give us.” Despite this, as Poole and Wyver point out,6 Brand makes no particular effort to align himself with the groups (such as the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy) which were taking shape at the party’s grassroots at around this time.

But without structural transformation, a redistribution of power within the party towards its grassroots and a new perspective drawing on the energies, capacities and ideas of those in the broader movement outside Parliament, Brand hits a brick wall again and again. His motion to Labour Party conference calling for nationalisation of the textile industry is passed in episode six, but it is the rightwing union official Reg Parfitt who points out the futility of his position, asking a rightwing Labour leadership to implement a policy in which it has no interest and for which it has no sympathy.

Griffiths also directs attention to the opaque, antiquated and anti-democratic nature of the British constitution, piercing through the fog of mysticism that surrounds it to highlight Labourism’s historic inability to analyse and address it in any way adequately. Last runs for the party’s leadership in episode nine, and being a quintessential parliamentary socialist, seems to view the process as a mere matter of wheeling and dealing between PLP factions in order to arrive at the required parliamentary arithmetic. But it is Chancellor Kearsley (a Denis Healey figure) who puts matters into perspective for him. After reeling off the familiar Labour right rap sheet of charges against the left - “economic chaos, social disorder, political massacre and economic suicide” - Kearsley gives a more concrete and compelling reason for denying his support to Last; that if he were elected to lead a party without an overall Commons majority, the Queen would not invite him to form a government. “Power indeed,” a crestfallen Last can only muse.

“Were You a Bastard When We Met?”

Far from being an orthodox Labour leftist, Brand is part of that generation of political activists whose worldview is moulded by the perspectives, analyses and concerns of the New Left. In Brand’s case this doesn’t just include Trotskyism (he is a former member of the International Socialists), but also the renascent feminist movement of his time.

In the second episode of the series, he brusquely refuses to judge a beauty contest before being forced to climb down by Jowett, while in episode four, he arranges (and, it is hinted, pays for) a constituent’s abortion after she is initially denied one - much to the chagrin of Jowett, wary of a potential backlash from the local Catholic electorate. He even gives a lecture at Ruskin College, critiquing Lenin’s patriarchal tendencies, and later engages in a fiery clash with Home Secretary John Venables (based partly on both Roy Jenkins and Anthony Crosland, and who later wins the party leadership contest) over the inadequacies of the Labour government’s measures to curb gender discrimination.

Despite Brand’s unequivocally pro-feminist political stances, his conduct towards the women in his life is less than exemplary, and he displays marked patriarchal tendencies of his own. He embarks on an affair with socialist-feminist activist and theorist Alex Ferguson as his marriage to Miriam collapses. Miriam bristles at the suggestion she should be expected to play the role of glad-handing politician’s wife, remarking acidly that she “didn’t marry [Brand] to put in appearances”. In episode four, as the two wait in the solicitor’s office to commence their divorce proceedings, Miriam is reduced - with much justification - to asking Brand: “Were you a bastard when we met?”

Alex, on the other hand, firmly rejects the notion that she should have to serve as a like-for-like replacement for Miriam once the latter is out of the frame. She astutely “discerns a puritanical and controlling streak in [Brand’s] personality” and soon realises that “having spent the last five years trying to rid [herself] of dependence on men”, she has effectively come to serve in that “surrogate wife” role she is so eager to avoid, even to the point of ironing his shirts for him (we also see Brand’s housemate Winnie Scoular providing him with bedsheets and offering to iron his trousers).

Garner has noted “Griffiths’ broader concern with the repressions and contradictions, the necessary but tragic hardening, that are required to move the revolutionary impulse (in Gramsci’s words) ‘between here and there’.”7. Griffiths himself has remarked that if socialist transformation was to occur in Britain, “it’s going to be led by people like Lenin, people prepared to sacrifice their private lives to public needs”.8 We see something of this in Brand’s own character - frequently chippy and taciturn, Alex criticises the passive-aggressive “man of stone routine” to which he is prone when unable to articulate his real emotions. But it isn’t just Brand’s own private life which he and his repressions sacrifice; again and again, the women around him are left to patch him up and send him back out into the world, until they simply can’t do any more. As one of Brand’s CLP comrades ironically remarks: “We can’t all be Lenin, but we can try.”

Eventually, Brand’s various insecurities - and the apparent expectation that she should play much the same role Miriam once did - become too much for Alex, driving her away: “You need guilt and dependence and deceit and mendacities like some people need heroin.” The two agree to part as friends, but Alex’s political influence endures thereafter and indeed runs right through the series. It is her socialist feminism that offers one essential route for pushing beyond orthodox left-Labourism, another consistent concern for Griffiths:

What I was trying to say throughout the series was that the traditions of the labour movement were inadequate to take the struggle further, and that we had to discover new traditions or revive even older ones. And that we had to seek connective tissue between electoral party politics, which still has a mystifying mass appeal, and extra-parliamentary socialist activity.9

Intriguingly, Alex also sketches out a proto-intersectional understanding of how different forms of oppression and exploitation are inextricably bound up with one another, and how this insight is integral to advancing the struggle Griffiths is concerned with - the struggle for socialism: “It’s foolish to imagine that you can win your rights without changing the whole map of inequity and injustice that even the most cursory reading of official government statistics… will show up.” This perspective was percolating through the labour movement at the time; it would be developed, expanded and elaborated upon in the following years in such seminal works as 1979’s Beyond the Fragments, informing and inspiring various campaigns - to name but a handful, the campaign for Black Sections in the Labour Party, Women Against Pit Closures, and Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners - which would drastically, and after a tremendous struggle, broaden the wider labour movement’s outlook and leave an indelible mark on it.

Brand has absorbed the socialist-feminist critique of Labourism into his own politics to a considerable extent; for instance, he rebukes Venables with the charge that patriarchal domination “is as characteristic of parties of the Left as it is of parties of the Right”. Furthermore, while denouncing the shortcomings of its anti-discrimination legislation, Brand stresses the vital role of concerted, militant extraparliamentary struggle in forcing the Labour government’s hand in implementing even these ultimately insufficient measures. But as Garner has argued, there remains a sense that the women in Brand’s life “serve as a backdrop for the more centrally realised struggles of men”.10 He draws attention to:

…a set of gender problems that Griffiths’s plays and films will never entirely escape: a privileging of the male as a site of political vision and agency, a fear of the female that (in the early work, at least) borders on the antagonistic, and a difficulty imagining the terms by which a cross-gendered mutuality might be achieved and sustained.11

Poole and Wyver, meanwhile, observe that the treatment of Brand’s personal life in the series “ends up in many ways inscribing Brand as a familiar kind of macho hero: the man with a remote wife and a ‘demanding’ mistress”.12 They note “a determination to use elements of the TV family drama to sugar the pill of politics in primetime”13 and it is this perhaps partly this approach - and partly also the budgetary constraints which cut the series from its intended 13 episodes to the 11 which were actually produced14 - which denies us a truly satisfying exploration of the tensions between Brand’s avowed feminism, his personal conduct and his concern with the broader limitations of Labourist thought and strategy.

While Griffiths depicts how the demands of the new, extraparliamentary social movements - including second-wave feminism - are making real inroads and thereby posing a serious challenge to the traditional perspectives of Labourism, Brand himself remains a prisoner of the patriarchal assumptions he sets out to challenge. It is hard, therefore, to take issue with Poole and Wyver’s verdict that the treatment of gender inequalities in Bill Brand ultimately falls short:

…it is one of the series’ great weaknesses that this strand, and its contradictory links back to Brand’s domestic arrangements, should have been phased out - leaving many of the issues it raised unresolved - to make way for the dramatic climax of the Labour leadership struggle and Brand’s role in it.15

“All We Need is a Few Bodies and We’re Away”: Medium, Framing, History

Bill Brand’s sixth episode begins in a TV outside broadcast van, where the crew are piecing together the opening sequence with which their later coverage of Labour Party conference will begin. Once their preparations are complete, the producer’s breezy remark - “all we need is a few bodies and we’re away” - is laced with irony. Here Griffiths brings home to the viewer how much of what goes on in politics is shoehorned into a narrative which is to a large extent pre-structured. For the waiting camera crews and journalists, all that remains is for the various participants in the conference’s proceedings - the PM, union leaders, MPs, delegates - to play the roles they have respectively been allotted in advance.

There is a consistent concern in Griffiths with the structuring and presentation of political narratives, and the inescapability of ideology in these processes. Griffiths’ 1974 BBC Play for Today, All Good Men, shares what Poole and Wyver have termed a “double focus, on a left critique of Labourism and television’s understanding of it”16 with Bill Brand. The play centres on Labour grandee William Waite, also a former miners’ union official, as he prepares to ascend to the House of Lords. Waite is to be the subject of a documentary profiling him and looking back on his career; the TV crew’s equipment is visible in the conservatory of his opulent country house.

It subsequently emerges, however, that Waite is being set up by the programme’s producer, Massingham, who “has a reputation for right-wing tele-journalism and… is probably setting Waite up for some kind of hatchet-job, dangling the carrot of a sympathetic interview-profile while all the time planning something altogether different.”17 Here we see Griffiths’ critique of both left-Labourism and the ideological manipulation of televisual presentation meshed together. Waite, the working-class Manchester boy turned Labour peer, remains so deferential he pathetically and credulously allows himself to be schmoozed by the upper-class charmer; it doesn’t occur to him that he is leaving himself open to being stabbed in the back. This observation from Tulloch seems pertinent here:

As Griffiths has intimated, the renewal of the ruling-class Right is so much simpler than that of the working-class left, partly because they have the power (which includes the power of articulation, through education, the media and so on), partly because they act purely instrumentally, without the self-doubt of inner dialogue.18

Griffiths understands intimately the powerful role television plays in shaping, guiding and constraining public discourse, including political discourse. He has placed great particular emphasis on working in television with a view to reaching the kind of mass (and, importantly, predominantly working-class) audience that both theatre and cinema simply could not offer, thereby potentially providing the playwright with the platform to make a meaningful political intervention:

Griffiths’ understanding of the medium underpins the strategies he has developed for working within it. And this understanding begins with that recognition of its importance: the theatre “is incapable, as a social institution, of reaching, let alone mobilising, large popular audiences… there are fewer cinemagoers in Britain now than there are anglers; fewer regular theatregoers than car-rallyers. For most people, plays are television plays, ‘drama’ is television drama.”19

With regard to television, Griffiths has invoked Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s theory that the sheer size of the communications system made “blanket supervision” and censorship impossible, leaving it prone to ideological “leakiness” and thereby providing opportunities for subversion, sneaking through counter-hegemonic perspectives and arguments.20 However, as Poole and Wyver presciently argued in 1984, changes in the media and televisual landscape, and the consequent decline of public-service broadcasting, meant that the operation of the market itself served to shut out the kind of perspectives Griffiths was trying to use television to put forward:

The kind of habitat in which Griffiths’ early and middle work had developed and thrived is, in short, in the process of being dismantled. The long-term prospects, with the advent of cable and satellite, are for the disappearance of any remotely protective environment as public service broadcasting makes way for the ‘self-regulating’ forces of the market.21

In addition to his preoccupation with television as a medium, framing and the ideological processes which underlie it, Griffiths also stresses the need for a proper reckoning with the victories, defeats, successes and failures of history so that the struggles of the present day are adequately informed. We see in Bill Brand that despite Brand’s obvious ambivalence towards Labourism and its heritage, including even that of its socialist wing, the series makes repeated references to key labour movement radicals of the past - including Nye Bevan, Tom Mann and William Morris - as well as crucial milestones in the movement’s history. This implicitly places Brand within that lineage, whether or not he is particularly comfortable inheriting the mantle.22

Griffiths also makes a point of invoking the events of 1931 - when the second Labour government collapsed over cuts to unemployment benefits, leaving four of its cabinet members to join a Tory-dominated ‘National Government’ - allusions to which appear throughout the series. He was far from the only one drawing the comparison between that crisis and the one facing Labourism in the 1970s; as the Callaghan government debated whether to accept an International Monetary Fund loan and its accompanying terms in November 1976 (three months after Bill Brand completed its run), Tribune published cabinet minutes from the critical period of August 1931, with Tony Benn ensuring that they were circulated to his own cabinet colleagues.23 Incidentally, in Bill Brand’s eighth episode, we learn from a radio bulletin that Chancellor Kearsley is in New York for talks with the International Monetary Fund.

Politically, Griffiths came of age in the late 1950s and was, as Garner points out, deeply influenced by the “socialist counter-history” of the period, particularly the emphasis on ‘history from below’ first pioneered by the Communist Party Historians Group. As part of his own attempts to contribute towards building a socialist counter-hegemony, Griffiths has sought to use television to offer reinterpretations ‘from below’ in opposition to those of the dominant ruling-class orthodoxy: “Griffiths understands history as a field of ideological contest, in which a politics of counternarrative and redescription must contend with official, class-bound representations of the past.”24

The socialist humanism of the early New Left is central to Griffiths’ politics. Influenced heavily by Raymond Williams and E.P. Thompson, Griffiths puts great stress on human agency and insists that we are not mere prisoners of history; that we have the collective capacity to change the world and shake off the fetters that shackle us. As Garner observes, Griffiths’ emphasis is “on socialism as something done by people for people”,25 and a central dilemma with which his oeuvre has consistently grappled is that of “whether socialist humanism had the focus and coherence to defeat capitalism”.26

This isn’t a quandary to which Griffiths pretends to offer any glib, comforting answers. The very ending of Bill Brand is a Griffiths signature, typically ambiguous and open-ended; we see Brand reading with some satisfaction a letter addressed to him noting the success of the Fight for Work campaign, with which he becomes prominently involved. But the conclusions he is drawing in his own mind are unclear to us - would his energies be better devoted to extraparliamentary work full-time, or is it his position in Parliament which enables him to help rally the forces of the movement outside, and to serve as its tribune? Griffiths leaves it to the viewer to turn this over in their own mind.

Even at a distance of four decades from when the series was first written, at a time when the Labour Party may soon find itself in government with arguably the most left-wing leadership in its history, these issues - the limitations of socialist advance via Parliament and the indispensability of extraparliamentary mobilisation to “take the struggle further” - remain utterly contemporary. Griffiths might not provide us with ready-made answers, but with Bill Brand he does at least prompt us to ask many of the right questions. We can hardly ask for more than that.

-

John Tulloch, Trevor Griffiths, Manchester University Press 2011, p98 ↩

-

Tulloch 2011, p87 ↩

-

Mike Poole and John Wyver, Powerplays: Trevor Griffiths in Television, BFI Books 1984, p72 ↩

-

Patrick Seyd, The Rise and Fall of the Labour Left, Palgrave 1987, p77-8 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p90-91 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p79 ↩

-

Stanton B. Garner Jr., Trevor Griffiths: Politics, Drama, History, University of Michigan Press 1999, p60 ↩

-

Garner 1999, p64 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p94 ↩

-

Garner 1999, p98 ↩

-

Garner 1999, p97 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p98 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p99 ↩

-

Garner 1999, p121 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p76 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p64 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p70 ↩

-

Tulloch 2011, p115 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p2 ↩

-

Garner 1999, p103 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p9 ↩

-

Poole and Wyver 1984, p79 ↩

-

Tony Benn, The Benn Diaries: 1940-1990, Arrow Books 2005, p377 ↩

-

Garner 1999, p9 ↩

-

Garner 1999, p23 ↩

-

Tulloch 2011, p4 ↩