How collectivism, mutual aid and political education formed a fundamental part of working-class community and culture.

Talk given at the panel A working-class party is something to be? at The World Transformed, 22 September 2019

I’m going to be talking about the history of socialist culture in some working-class communities in the early twentieth century, and its relationship with the Labour party. This is obviously a massive topic, which I can only give a brief introduction to right now. I’ll be drawing on my own experience growing up in the Welsh Valleys, which is an outstanding example of a place that was first defined by its industry – ironworks and coalmines – and then a place that, since the 1980s, has been defined by the lack of industry and the lack of any replacement for this economic base. But the history of British mining communities – not just in Wales but also in the North East and parts of Scotland – provides a valuable example of how ordinary people developed a particular kind of culture, institutions and infrastructure from scratch, an ecosystem based around mutual support and collective provision in a way that we may think of as proto-socialist.

The first thing to say is that this infrastructure was developed largely through industrialisation and industrial organisation. Trade unions of course predate the Labour party, they have been around for over three hundred years as the Industrial Revolution called a mass industrial working class into being in this country, and these workers gradually began to organise for better working and living conditions - including, eventually, founding the Labour party as an ultimate political expression of the needs of organised labour. By the early twentieth century, industrial communities had developed individual union branches and lodges based on particular workplaces and localities – and these organisations, particularly in coalmining communities, developed a welfare, social and cultural role.

Their welfare function was particularly important because at this time there was little or no state provision for financial support or healthcare, so communities developed their own. The basic idea of this was that individuals paid a small amount of money into a central fund, which then entitled them to help or support or the use of a service when they needed it. So in the years before the NHS, this system allowed unions to organise and pay for the building of, for example, retirement homes and convalescent homes – so when their members became ill or injured or when they retired – after years of paying their dues, paying a small amount of their wages into funding these institutions, they could spend some time there being provided for. In the 1890s, the mining town of Tredegar set up a Medical Aid Society which was funded by subscriptions from local people, and which provided medical care free at the point of use. When the Labour MP Aneurin Bevan, who was also from this town, came to establish the NHS, this was the model he drew on – he used this very simple, localised model of socialised health care as part of a national blueprint.

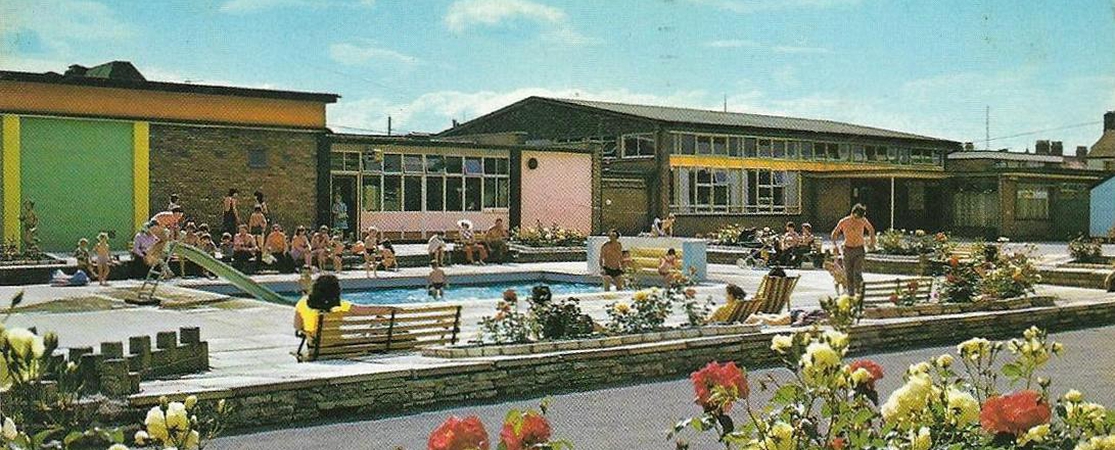

In terms of culture and leisure, workers campaigned for paid holidays, which weren’t something taken for granted or handed out by bosses, they had to be fought for. Unions negotiated holiday savings schemes with employers and the government which enabled pits to close for a week in the summer with a guaranteed payment to each miner. Once this system was in place miners would organise their own holidays or day trips, as a community, since they’d all be off work at the same time, and sometimes established their own holiday camps. There were also local festivals or carnivals organised at various points in the year: the example you might know is the Durham Miners Gala which is still with us after 150 years – these galas took place throughout the country and were community days out which had a social and a political function. There was also organised music, sport and drama, with particular bands or sports teams attached to particular pits, and local operatic or dramatic societies. This was a culture that drew on local solidarities, the idea of belonging, forms of civic pride, as well as an extension of the collective resources involved in industrial organising.

A fundamental, material part of this infrastructure was something called the miners’ institute. These were buildings, sometimes known as working-men’s institutes, or workmen’s halls, which were constructed in industrial communities as a multipurpose social and cultural space. Again, these places were built on collectivist principles, with workers paying a proportion of their wage into a communal fund, usually something like a penny per week, to pay for the construction and running of the building – sometimes even carrying out the construction work themselves. This then entitled them to use it. These buildings were created in order to be part of the community, part of the social fabric: they could be used for community meetings or to hear political speakers, there was usually a bar or a space for dancing, a pool or snooker room, a cinema room, so it was a social, cultural and political space at once.

Crucially, these buildings also usually contained a library and reading room, where members could freely access both books and newspapers. This point highlights the tradition of self-education that was also important in these communities: the idea of educating yourself, the autodidactic tradition which defined so much of this early working-class culture. This is something that’s been lost sight of in an age where education is now associated with class mobility, “aspiration”, and transcendence into the middle class. When people say ‘education’ they tend to mean ‘university education’ and to assume that this somehow excludes working-class people. But in early working-class communities, self-education and access to knowledge could be seen as an obvious part of the cultural fabric – you gained knowledge in order to understand the world and understand your own conditions, not necessarily to transcend your class individually but to improve yourself as part of that class, and to collectively improve your situation.

Miners’ libraries were a central part of that tradition of political education, but trade unions also offered more specific routes into education and political training: they established their own educational institutions like The Central Labour College in London, supported by miners and railway unions, which ran from 1909 to 1929 and provided independent political education for union members. Unions also trained their members to be advocates for each other in tribunals and in negotiations with bosses and government, which required knowledge of law and regulations as well as rhetorical skills.

This centres on the idea of workers becoming political representatives of their class. Working-class MPs like Bevan, by the time they got to Parliament, had experience of working in mines or factories, they had practical knowledge of working conditions as well as knowledge of Marxist and socialist theory through the use of miners’ libraries and resources for self-education. Applying these ideas to their own life and what they saw around them developed their politics. This was praxis, not merely theory. This demonstrates, again, how the Labour party could function on one level as an ultimate expression of working-class political education – in a way that’s now almost entirely lost.

Because so much of this culture and the communities that created it were based around specific industries, it was peculiarly vulnerable to economic change. The end of heavy industry and the breaking of the unions in the 1980s therefore had a catastrophic effect which is difficult to overstate. Deindustrialisation meant the loss not only of the economic basis of an area, but also of the social and cultural pillars of support that had previously defined working-class communities. Things like the miners’ institutes were left to decline; without wages coming in it was no longer possible to financially support the kinds of previous initiatives that had existed. This devastation was deliberate, of course; it was an attempt by the Thatcher government to eradicate a particular culture, lifestyle and political ecosystem along with an industry.

In political terms, deindustrialisation weakened the Labour party’s commitment to working-class voters: as the country transitioned from an industrial economy into a largely service-based economy, Labour’s strategic response was to converge ideologically with the centre ground, attempting to court middle-class voters. The party’s development after the Miners’ Strike focused on distancing the party from its historical basis in industrial culture, and this tendency of course reached its peak under Blair. Throughout the 90s, we had the social and cultural aftermath of the 80s as well as the economic effects of structural unemployment, the lack of prospects – all while New Labour in government were presenting the country as being “all middle-class now”.

Austerity then compounded the state of post-industrial areas, further reducing resources and prospects, rolling back the gains made through the welfare state and removing the remaining outposts, like libraries, that still functioned as educational and community spaces. And throughout these years too, in cultural terms, you had the crisis of class representation in media and politics, which allowed a stereotyping of the working class which erased history and awareness of these previous traditions, and made it difficult to articulate an alternative or even to believe in one.

Given all the defeats and the damage that working-class culture and the idea of working-class community have taken over the past thirty years, rebuilding or renewing it is a huge task. But at the same time it’s important not to succumb to destructive or fatalistic forms of nostalgia. First of all, let’s not uncritically eulogise this history and these communities – we know they weren’t utopias. For all its benefits, this way of life could be stifling, claustrophobic, patriarchal, and reactionary in many ways, and historically we know that working-class individuals could find it generated alienation, dissatisfaction, boredom and resentment as much as it provided economic and social security.

Equally, and conversely, it’s important not to write off contemporary post-industrial areas as being hopeless irredeemable wastelands. Art, culture, education and forms of community support still exist in these areas, despite their economic devastation; in some former mining communities, the institutes have been able to rebrand themselves as entertainment or arts centres. We shouldn’t fall into the trap of ignoring the working-class agency and capacity that still exists; if we are to have some sort of cultural renewal, it is this agency that we need to draw on.

When we think about this it’s also important to acknowledge the working class as it looks today. The heavy manufacturing industry on which early twentieth-century working-class culture was built is gone, almost certainly forever. We can never exactly replicate what has been lost. (Given the broader environmental and ecological toll taken by mining, and the rate of illness, injury and early death among miners, it’s debatable whether anyone would want to.) The contemporary working class contains sections of workers who have historically not been unionised – either retail and service workers who have traditionally been considered too transient and inchoate a workforce to organise, or ‘new’ forms of precarious and atomised workers in the gig economy. But in the last few years it’s these same sectors that have been emerging as militant and organising successfully – we’ve seen actions by workers at Deliveroo, Greggs, Picturehouse, McDonalds, Wetherspoons and elsewhere.

It’s also the case that these sectors consist much more prominently of workers who have historically often been neglected by unions and not spoken of as part of the ‘traditional’ working class, even though they have always been part of the workforce: female workers, young people, migrant workers. Sections of both the right and the left are prone to presenting a narrow idea of the working class as consisting entirely of white, male (post-)industrial workers – when this has never been entirely accurate and isn’t accurate now. This recognition should remind us that there is no contradiction between fighting to improve material conditions and acknowledging how material conditions are compounded by dynamics of race and gender. Working class lives are inherently intersectional and always have been, understood as a result of lived experience.

The early twentieth-century working-class culture I’ve been describing forms only one strand of the culture and politics of the British working class, but it is, I think, valuable and useful. I’d like to finish off by referring to the Durham Miners’ Gala again. It’s been strange over the past few years to see it revived and reinvigorated along with the Labour left, and to see the Labour leadership now reconnecting with it after deliberately breaking the link with it in the Blair and Brown years. The miners’ gala demonstrates the existence of an enduring or residual working-class culture. It still has its traditional form, being a community day out with political and social functions, and it acknowledges these past traditions of working-class cultural and political achievements. But its content changes, whether offering international solidarity or opposing austerity, to address the priorities of the labour movement at any given time.

The line associated with the miners’ gala - ‘The past we inherit, the future we build’ – is, I think, always applicable. Rebuilding a socialist working-class culture requires recognising what worked in the past, but also recognising changed conditions, and shaping our outlook and our organising in order to take account of that.